Diving accidents are rare, yet in almost every case stupidity features highly and Saturday’s dive was no exception. We were a group of seven. Three were former students with various qualifications (minimum Advanced), all having done between 20 and 100 dives. All regular divers with me, they were just tagging along for a fun dive. I had three students doing a deep dive for their Advanced diver qualification. All three had completed most of the dives for this course and deep was one of the last dives. I had assessed all three during previous dives and did not anticipate any problems. Cecil, very capable, excellent dive skills and safety concious; Mark, very capable, good dive skills and Diver X, also capable and on two previous deep dives had displayed good watermanship.

So what went wrong?

We descended in a strong current, staying reasonably close together and doing a nice safe slow descent. (I am not a fan of dropping like a brick.) I paused at 20 metres to make sure there were no signs of stress from anyone. Tami was a little slow in getting down but her buddy was watching and of all the group Tami rates high up on the best of the rest list so I was not concerned. The visibility was good, 10 – 12 metres and I could see from everyone’s bubbles that they were all breathing in a relaxed manner.

We dropped to the bottom, and I handed slates to the three Advanced students, slates with a few questions, a bit of maths, and a simple puzzle. This task is a good indication of nitrogen narcosis and a diver’s state. Some of the questions on these slates are ‘”How much air do you have?” and “What is your depth and who is your buddy?”

I time this exercise, so I check my dive computer during the process. This tells me if the depth answer is right, and at the end of the exercise I ask each diver to signal their air supply. Diver X got most of the answers wrong, and more to the point his air pressure answer was 10 bar. I asked him to look at his gauge as everyone else had close to 200 bar. He indicated he did not understand his gauge so I looked at his gauge and it was ZERO.

He then turned and swam away from me towards Cecil, pointing at Cecil’s body. Having someone point at your torso tends to make a person look down to see what he is pointing at. At this point I had caught him up and started to turn him around. He then spat out his regulator and at this Cecil realised there was some problem and perfectly executed the raised arms so his octo was in clear view.

I shoved my regulator in Diver X’s mouth and looked at his eyes – he had no idea of what was going on. I then gathered the group and we started to ascend with Diver X on my octo. At one point I had to bang him on the chest to get him to understand he should hold onto my BCD as he refused to do so and twice drifted off and lost the regulator. We did a short safety stop and ascended. He did not orally inflate his BCD on the surface so I did it for him.

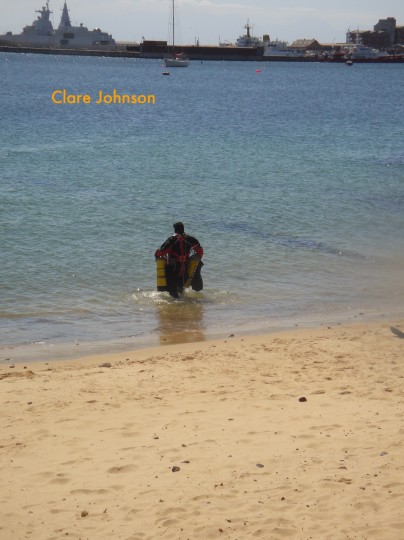

I am extremely grateful to Grant for racing the boat over and getting us out of the water quickly, as we surfaced far from the buoy line (owing to the howling current) and the unexpectedly rapid ascent (and the fact that my hands were occupied holding onto Diver X) meant that we hadn’t deployed our SMBs. The dive site we were at, the wreck of the SS Cape Matapan, is very close to the shipping lane into Table Bay harbour and very exposed. The southeaster was strong and the sea was choppy with fairly large waves making divers on the surface without SMBs very hard to spot.

What do we learn from an incident like this?

- Check, check, check your gear. I doubt Diver X checked his equipment before the dive. Second, he did not do a proper buddy check.

- Keep your skills sharp. Diver X has forgotten many of the skills he was taught when he did his Open Water course. Refreshers exist for a reason.

- Be fit to dive. Get enough sleep and don’t party the night before a dive – SPECIALLY a deep one, where there is no room for error. DON’T come diving if you’re hung over or stoned.

- Be alert before and during the dive. Check your pressure gauge before you stow your gear on the boat, when you kit up before rolling into the water, again when you get to the bottom, and frequently during the dive.

And, if you require a dive buddy with exceptional skills, then Cecil is your man.

I know you will all blame nitrogen narcosis for this incident, but on the way up I stopped at 15 metres, again at 10 metres, and again at 5 metres, and there was no change in Diver X’s behaviour. I had to descend from 2 metres back down to the group doing their safety stop and get them all together so we could surface as a group as we were diving on the edge of a shipping lane (I was concerned that we had possibly drifted into the shipping lane in the current) and I had not surfaced with a SMB as I could not release my grip on this diver to deploy the SMB.

What most people don’t realise is that when you don’t take dive safety seriously you almost always put others at risk. I had five other people with me, their safety being my responsibility. We risked surfacing in a shipping lane, without an SMB in less than perfect surface conditions (to put it mildly). All in all other people were put at risk due to the casual disregard for safety by one diver. Don’t dive stoned, hung over or when not serious: not with me and not with anyone else.

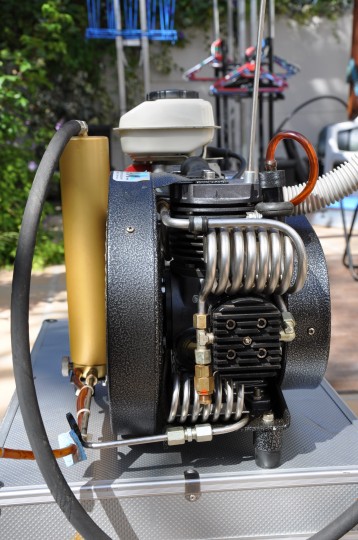

I’m left with one cylinder half filled with sea water, one salt-filled pillar valve, and one first stage and two second stages requiring complete rebuilds or servicing. And hopefully some thoughtful divers who all learned something today.