This post follows on from my review of Global Perspectives on the Biology and Life History of the White Shark. That book (a collection of scientific papers) is divided into three sections, and I’m going to highlight papers that I found particularly interesting in each of the sections. Here’s the first series of posts I did, on Biology, Behaviour and Physiology:

There are several known white shark “hotspots” around the world (of which South Africa has a couple) where fairly extensive work has been done to tag and monitor sharks that frequent these locations.

Fine-Scale Habitat Use by White Sharks at Guadalupe Island, Mexico – Domeier, Nasby-Lucas, Lam

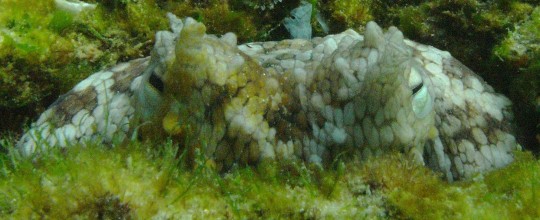

Guadalupe Island, about 300 kilometres off the Mexican mainland in the north eastern Pacific Ocean, is one such hotspot. It is a pupping and haul-out (resting!) site for three kinds of seal and sea lion. The seals come and go, fluctuating by species throughout the year. The researchers found that the sharks moved around the island seasonally, positioning themselves near the current aggregation of whatever species of pinniped was peaking. They also noted that during certain months the sharks dived deeper around the island, possibly also corresponding to predation on a different kinds of seal.

Sex-Specific Migration Patterns and Sexual Segregation of Adult White Sharks, Carcharodon carcharias, in the Northeastern Pacific – Domeier, Nasby-Lucas

The Northeastern Pacific White Shark Shared Offshore Foraging Area (SOFA): A First Examination and Description from Ship Observations and Remote Sensing – Domeier, Nasby-Lucas, Palacios

White sharks tagged at both Guadalupe Island and in central California have been shown to spend time each year at a location known as the “shared offshore foraging area”, or SOFA for short. The first of these papers determined the seasonal pattern of shark presence at the SOFA. The males can spend as much as 9-10 months offshore, in a moderately concentrated area (95% of the tagged sharks stayed in an area of diameter 1,000 kilometres, so not THAT concentrated). The SOFA was observed to be a cetacean “dead zone” inhabited only by sperm whales and no other cetaceans. The female sharks did not spend much time in the SOFA, but instead roamed through a very large stretch of ocean that overlapped with it somewhat.

There are fairly extended periods of time when the sexes are completely segregated. The authors propose one or two reasons for this. One is that female white sharks grow much larger than the males, and thus have different energy requirements. This may cause them to forage elsewhere.

The second paper recounts the results gained from sailing a research vessel out to the SOFA, performing transects, scanning for marine animals, and analysing other aspects of the site. The vessel found the area to be characterised by downwelling, no major temperature shifts, very little plankton, and very little horizontal movement. It also found no small cetaceans, but identified sperm whales and three kinds of spawning squid. (White sharks are known to eat squid.) The presence of these apex predators (white sharks, sperm whales, squid) suggests that there’s a lot more biomass supported in the deeper water that wouldn’t be evident from a surface survey.

A New Life-History Hypothesis for White Sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in the Northeastern Pacific – Domeier

The tagging studies performed at the Farallon Islands and at Guadalupe Island off Mexico have allowed a new hypothesis regarding the life history of white sharks in the north eastern Pacific. Domeier speculates that white sharks may begin their lives in the shallow waters of southern California and may spend their first year in the region. This corresponds to an area where the Monterey Bay Aquarium has acquired juvenile white sharks caught by fishermen for their exhibits.

As the young sharks get larger, they can tolerate cooler water and are thus able to dive deeper and migrate further. Their diet changes from fish and invertebrates to marine mammals such as seals. As they mature, the males begin an annual migration to either Guadalupe Island or to the Farallon Islands and surrounds, off central California. Males from both the aggregation areas visit the SOFA mentioned above, while females range more widely.

The females only visit the aggregation sites every second year, presumably because of an estimated 18 month gestation period during which they spend 15 months at sea. It is believed that mating takes place at these aggregation sites. The females then return to the coastal regions off southern California and Mexico, between May and August, to give birth. They then return to one of the aggregation sites.

This kind of synthesis of previous studies enables the identification of regions where sensitive white shark populations may exist, such as the pupping grounds off California.

~*~

Several papers in this section are devoted to the behaviour and movements of juvenile white sharks off Australia, with a view to better understanding their movements in order to minimise interactions with beach users.

Seasonal Sexual and Size Segregation of White Sharks, Carcharodon carcharias, at the Neptune Islands, South Australia – Robbins, Booth

The sexual and size differences between white sharks present at the Neptune Islands in southern Australia was studied by the authors. They found similar sexual segregation to that observed in the north eastern Pacific studies. They found that larger white sharks visited the islands during the austral winter and spring (June to September). The female sharks seemed to prefer warmer water temperatures, perhaps as an aid to embryonic development when they are pregnant. Far more male sharks than females were identified (for mature sharks, the male:female ratio was 12:1).

The Third Dimension: Vertical Habitat Use by White Sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in New Zealand and in Oceanic and Tropical Waters of the Southwest Pacific Ocean – Francis, Duffy, Bonfil, Manning

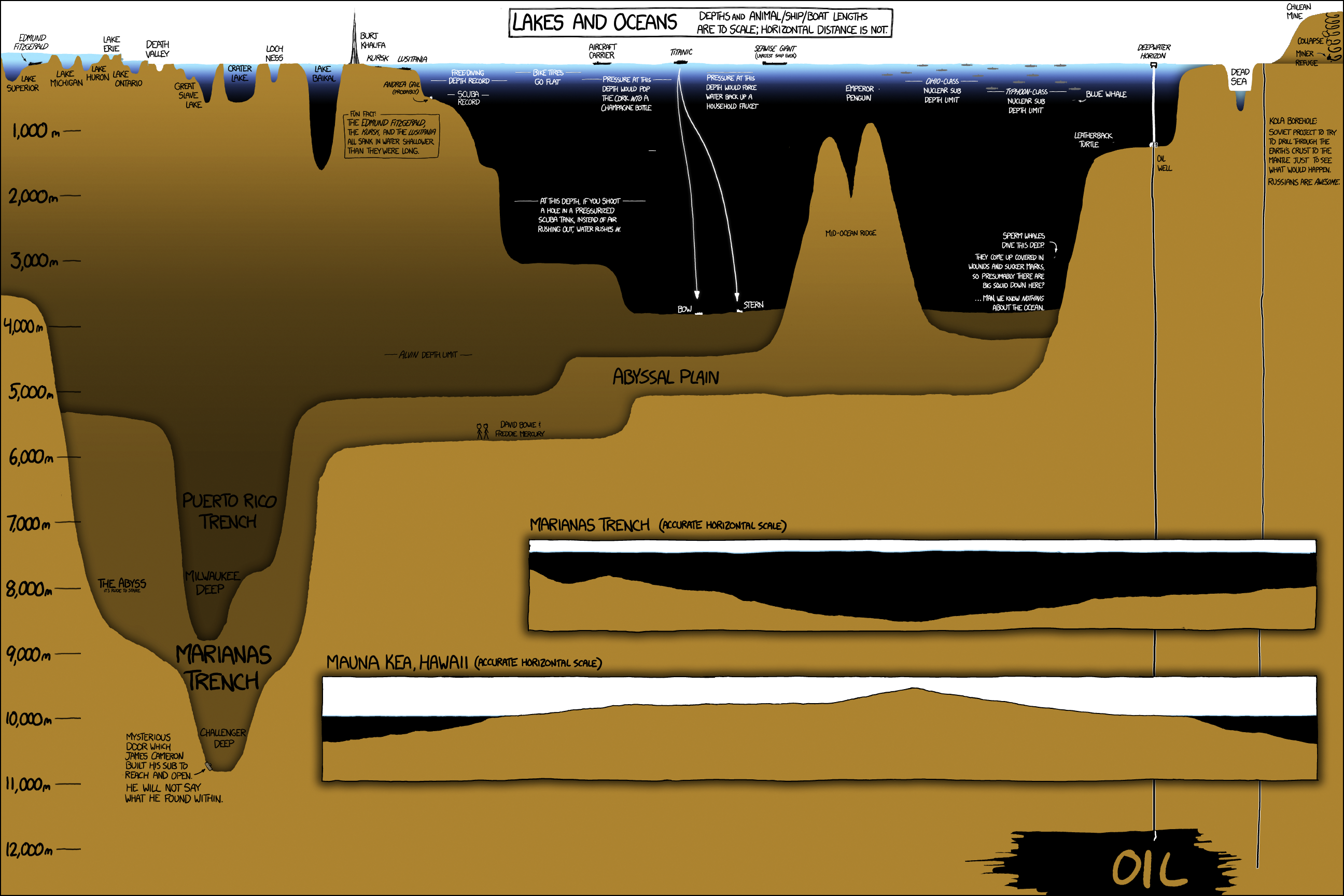

The authors analysed the data from 25 white sharks tagged in New Zealand, as they commenced long-distance migrations across a wide range of habitat types to the south west Pacific Ocean. While on the continental shelf the sharks remained in water less than 50 metres deep (this counts as “shallow” if you’re a marine animal), but during the open ocean migration phases they alternated between being on the surface and doing dives to depths between 200 and 800 metres. One shark went to 1,200 metres. A reminder that it’s pretty much pitch dark down there once you get beyond about 200 metres!

Once they entered the tropical regions, the sharks remained in the top 75 metres of water but coninued to dive deeply. Their dives often corresponded to a 24 hour cycle, with the sharks spending more time diving during the day than at night. The reasons for this could be many, but the sharks may have been navigating at night, or feeding on the creatures that pursue the plankton migrating towards the surface in the darkness.

The behaviour varied widely among the tagged sharks, and more studies in other regions will enable better understanding of why the sharks behave as they do in the various ocean habitats.