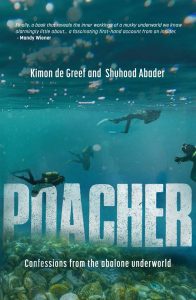

Poacher: Confessions from the Abalone Underworld – Kimon de Greef and Shuhood Abader

Abalone (perlemoen to locals) are inoffensive, slow moving marine snails, with frilly grey bodies covered by a knobbly shell that doesn’t look like anything special until you find an empty one on the beach and see the mother of pearl interior, polished for years by the body of the now-dead snail. Some people like to eat them; in Asia, many people like to eat them, and they are seen as a status symbol. They are farmed, at enormous expense and for staggering profits, at several locations along South Africa’s coast. When we visited an abalone farm in Hermanus several years ago, the tour guide told us that the demand for abalone from the east is essentially “limitless”. You can imagine, if you don’t know already, the financial temptation that such a creature might present.

Kimon de Greef is a South African journalist with a longstanding interest in perlemoen poaching and other forms of illicit trade. His reporting on abalone poaching has been longstanding, nuanced and detailed – one example here, and another here. A 2014 report (pdf) he wrote for Traffic, the wildlife trade monitoring network, is also worth a read. The second author of Poacher, Shuhood Abader (not his real name), is a former abalone poacher, and this book is his story.

Rather than a focus on statistics and an analysis of the scale of the abalone poaching problem in South Africa and how to fix it, Poacher comes at the issue in a deeply personal way, thus forcing us out of our righteous outrage and into the uncomfortable space of empathy with someone whose actions we disapprove of. We hear Abader’s story in his own words, with context provided by de Greef’s reporting and analysis.

Being a South African today is complicated. Our history gives none of us a free pass to relax into ignorant bliss, simple judgments or two dimensional interpretations of where we find ourselves and where we are going as people and a country. Yes, it might seem tiring for those of us whose privilege is showing, but the last several hundred years of our history demands a reckoning and we ought to show up for that, no matter what it requires. This reckoning extends beyond hard conversations and simple matters of ensuring everyone access to healthcare, education, property, jobs, credit, public spaces, and the like. It extends even to nature reserves and marine protected areas, those spaces that we view as sacred and untouchable. (I remind you of this discussion we had on the Tsitsikamma MPA – similar complexities exist for many, if not all the wild spaces in South Africa.)

Marine poachers are fairly visible to the scuba diving community. (Recreational divers are even mistaken for them on occasion.) The ISS has published two in depth reports (Steinberg and Goga) on the subject, some years apart. Abalone poaching is one of those issues that seems to cause particular outrage among scuba divers and the ocean-loving community, and this is, to some extent, understandable. Poacher, however, asks us to set aside that outrage and to learn another side to the story. This may disturb your equilibrium – the more the idea of there even being “another side” troubles or enrages you, the more strongly I recommend you read this book.

When Poacher was released there was excellent media coverage, which you should check out to get a flavour of the topic, and the two authors. Examples are this Daily Maverick article, detailed coverage by The Guardian, and an interview with one of the authors here. You can even read extracts from the book at the Johannesburg Review of Books, on News24, at Wits University’s Africa-China reporting project, and at the Daily Maverick. There’s a radio interview with de Greef here.

Please read this book. Get a copy at your local bookstore, online in South Africa here, or on Amazon.

If you read this in time, Kimon de Greef is discussing the book on the evening Thursday 4 July 2019 at Kalk Bay Books – phone them for details and to RSVP (essential).