This information could possibly used to certify me insane, but I will risk it.

Very little research has been done about this but I (as have many others) have always believed that different creatures begin to warm to divers. There are many stories of specific ocean creatures being named, recognised and often visited by many divers.

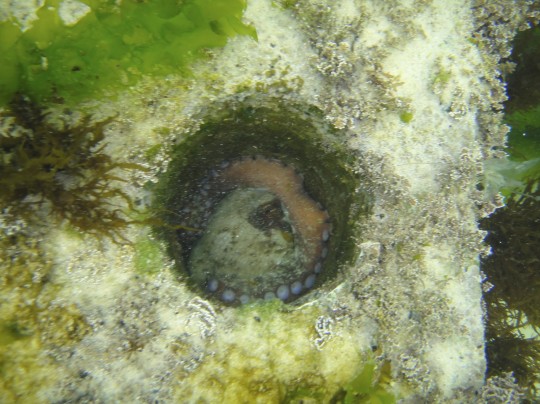

Octopus

Several octopus at Long Beach for example live in holes on the pipeline and no matter what if you go by in the day they will be there.

Often, on night dives,there is no one home as they are off feeding, probably close by, but due to the darkness we don’t see them. This is how they move around at night.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mAL6Nld69vI&w=540]

Brindle and potato bass

Sodwana Bay had a brindle bass, seen by many divers year after year at the same dive site. This huge creature was very friendly and enjoyed interacting with divers. Many creatures in the ocean are fiercely territorial and once you have found them and discovered their territory it is easy to spot them as they seldom go far.

Whilst working in Mozambique I too visited the same reef sometimes four or five times a day on a busy weekend, showing different groups of divers the same ”locals” on the reef.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyq6qcByx6A&w=540]

This video shows a huge potato bass that I believed was always waiting for us to drop in. This potato bass is easily recognizable by the fact that she has only one eye. You could not just swim past without giving her a tickle as doing so would result in her following the group all down the reef. Ascending to the safety stop you would see her race back to the start of the reef where she knew the next group would be dropped.

I am convinced of this as on the odd occasion that the weather would present us with a reverse current, we would drop down on the opposite end of the reef and there she would be.

Moray eels

“They bite” is what any diver will tell you. Well they do, however I believe this particular black cheeked eel warmed to me. I visited her every day for about six months. The first few weeks I just looked, then the next few weeks I offered my hand, it got bitten, severely several times and the resulting injuries required a few weeks of looking only. From this video clip, heavily edited, its clear the aggression shown in the first few weeks waned, became less severe, and eventually slowed right down to a nibble without breaking the skin… Was she warming, becoming more friendly or just getting so tired of my annoying hand in her face that she didn’t want to bother? You decide.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ti4xoPWSztU&w=540]

A rather large honeycomb moray also fond of a chin tickle:

Peanut & Butter

The reason for the preceding information is to justify my fondness for two little fellas I met at Long Beach while Kate was doing her Zero to Hero course. They are called Peanut (a juvenile double sash butterflyfish) and Butter (a juvenile jutjaw).

I first spotted them a couple of months back and every time I go by on a dive I take a peek to see if they are still there. Being as small as they are there is a real risk they may end up as lunch for someone, but for now we will monitor their progress and watch them grow.