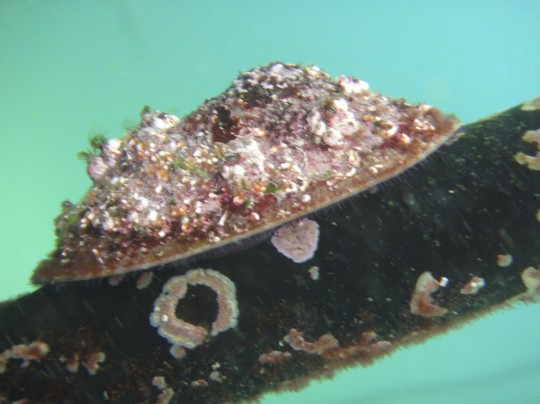

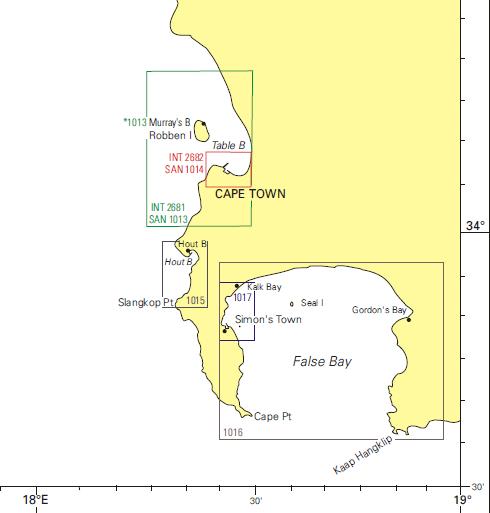

Shark Alley is a special and unusual dive site just south of Millers Point. It is an aggregation site for broadnose sevengill cowsharks, predators who feed on seals and a variety of other animals. They can grow to three metres in length. These sharks seem to use this site as a resting area (though we aren’t sure – research is ongoing) and their behaviour is typically docile and relaxed. For this reason it is a great place to dive, as the sharks come close enough to get a good look at them but do not behave in a threatening manner.

There has never been a serious incident involving a diver and a shark at this site, but there have been a few incidents. Clare has had her pillar valve gnawed on by a feisty young male shark while on a dive here a few years back, and early in May a diver was bitten on the arm by one of the sharks. That latter bite made the newspaper (the shark drew blood and the NSRI was summoned), but I am sure that there have been other more minor incidents here that didn’t get reported.

This got me thinking about a protocol for diving with these animals. Shark dives all over the world are governed by safety protocols and guidelines, usually put in place by dive operators themselves (examples here and here). We do have a set of standards that we adhere to when visiting this site and mention in dive briefings, but I’ve never written them down all together before. I am a firm believer in self regulation, whereby the industry regulates itself so that we don’t end up with a bureaucrat in an office telling us we can’t dive with cowsharks without (for example) a special permit, or (heaven forbid) ever again!

So here’s our protocol – how we choose to regulate ourselves when diving this site. It’s not a set of hard and fast rules that everyone has to follow, but it’s how we choose to approach dives at Shark Alley, a little bit like Underwater Africa’s diver code of conduct, but for cowshark diving. You are welcome to use these principles yourself, and I’d like to hear any suggestions you have to improve them or for points I may not have thought of.

- Do a positive entry (i.e. with your BCD fully inflated) if you are diving off the boat, so you do not risk landing on a shark in mid water. If there is a thermocline, the sharks typically swim above it, and may be shallower than you expect.

- Descend slowly in a controlled manner, looking below you at all times. Ensure that you are carrying sufficient weight (you should be able to kneel on the sand if necessary).

- Do not make any physical contact with the sharks. Do not try and stroke them as they swim by, and do not hang on their tails or dorsal fins.

- Do not feed the sharks. Don’t carry anything edible (sardines, for example) in your BCD, and do not chum from the boat. This includes washing the deck off at the dive site if you’ve just been fishing or on a baited shark dive. Chumming is both illegal (you need a permit) and unsafe, especially if there are divers in the water.

- If you have students in the water, perform skills away from the sharks (if possible, avoid conducting skills at this site).

- Some sharks will show a keen interest in your camera and flash or strobes. Do not antagonise them by putting a camera directly in their face. If a shark is showing undue interest in your photographic equipment, hold off taking pictures for a moment while it swims away.

- Move out of the sharks’ way if they swim towards you. (Here’s a video of Tami doing just that.) Cowsharks are confident and curious, and often won’t give way to divers. Respect their space and move far enough away that they won’t rub against you or bump you as they swim by.

- Be alert for any strange behaviour by an individual shark or the sharks around you. Be aware of your surroundings and don’t become absorbed with fiddling with your camera or gear. If a shark does become overly familiar (bumping or biting), gather the divers together in a close group and abort the dive in a controlled manner.

- Do not dive at this site at night or in low light. This is probably when cowsharks feed (though we aren’t sure), and as ambush predators their behaviour is likely to be quite different in dark water when they’re in hunting mode.

- Do not dive at this site alone. When diving in a group, stay with the group and close to your buddy.

I am not writing this protocol down to make people afraid of diving with cowsharks in Cape Town. But I do think it’s important to remember that this is a dive that needs to be taken seriously, with safety as a priority. Because we can visit this site whenever we want to, it’s tempting to become blasé about what an amazing experience it is, and also about the fact that these are sharks that need to be respected.

In conclusion! Unlike great white sharks, cowsharks (and blue sharks, and mako sharks, and and and…) are not protected in South Africa, so it’s not illegal to fish for them in permitted fishing areas (i.e. outside no take zones, etc). One of the cage diving operators in Gansbaai even used to use cowshark livers in his chum… If you want to make a difference in the lives of cowsharks and ensure they’re still here for us to dive with in future decades, consider writing a letter to the relevant government minister (make sure it’s the current one, in the new cabinet) and also to the shadow minister from the opposition party, requesting protection for more shark species in South African waters.