I’m back from an overly lengthy blogging hiatus (sorry) to resume a function that I’ve performed once or twice in the past. Fortunately I have had octopus on my mind and had already started posting again, and so we aren’t doing a standing start.

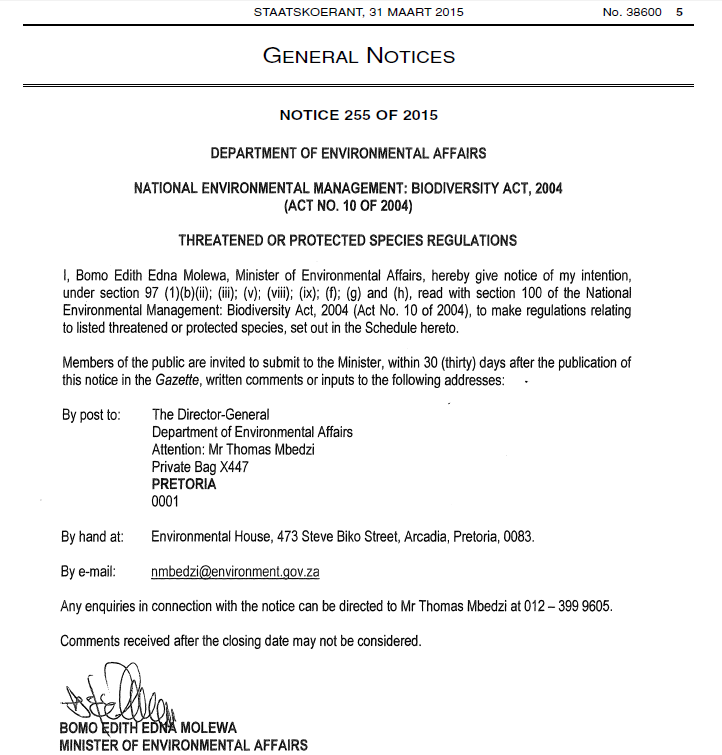

I have read some legislation so you don’t have to, will try to tell you what it means, and – if necessary and possible – I will tell you how to object to it. Someone has to do it, and my mathematician’s brain actually quite likes trying to follow the logic of these documents. (Previous efforts along these lines include this one on seals, this one on new MPAs, and this one on the Tsitsikamma MPA.)

The new legislation this time is actually two documents that were published in the Government Gazette on 30 May. Before we get into these two most recent documents, however, it may be instructive to look back at the original act that they refer to.

National Environmental Management Act: Biodiversity

The act in question is the National Environmental Management Act: Biodiversity, number 10 of 2004 (pdf full text). We will call it NEMBA for short. This act is a framework which provides for the management and conservation of South Africa’s biodiversity, as well as the protection of species that require or deserve it, the fair apportionment of benefits that may arise from the country’s biological resources, and the establishment of SANBI.

The important sections of this act for us, right now, are sections 56 and 57. Section 56 empowers the Minister of Environmental Affairs to publish in the Government Gazette, from time to time (at least every five years or more often than that), a list of critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable, and protected species. A species may be protected but not endangered; a case in point is the Cape fur seal.

I am not knowledgeable enough to state confidently that the extract above is using a set of widely accepted definitions here. However, this list of definitions from (critically) endangered to vulnerable does look a lot like the IUCN categories for classifying species at risk of extinction.

The next section talks about activities involving species that fall into one of the categories defined in section 56. Provision is made here for the Minister to define activities that are “restricted”, and section 57 specifies that if an activity is restricted, a permit is required in order to perform it. The definition of restricted may vary from species to species (but I am getting ahead of myself).

Finally, section 97 of NEMBA, which is on page 40 of the PDF file I linked to above, empowers the Minister to make regulations dealing with a large number of matters, mostly permits, and threat-minimisation for threatened ecosystems.

Marine Threatened or Protected Species regulations

With that preamble, let us turn to the most recent regulations, which were made in terms of section 97 of NEMBA and pertain to threatened or protected marine species. They come in two parts. The first (pdf – all page numbers below refer to this file) is a set of regulations, mostly related to permits. This sounds very boring, but there are some interesting bits, and an important definition. Definition first:

This is a very important definition (from page 10-11) as it essentially determines what is legal and what is not in terms of the act, and one that I think is perfectly reasonable. You can still take photos of and dive with seals, turtles and most sharks. Whale sharks and basking sharks are not to be bothered up close, though.

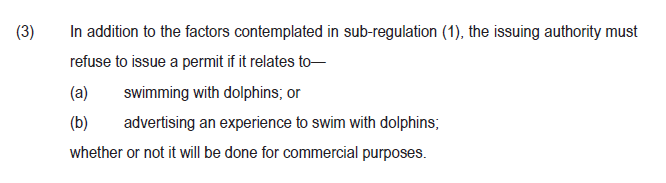

Notice also that we now have a definition for harassment of dolphins; it has been my understanding (perhaps incorrect) that until now there has been a loophole in that there has been no legal prohibition on approaching dolphins in a boat, whereas boats must stay at a distance of 300 metres away from whales. I can think of other things I have seen boats doing with dolphins – such as corralling them by speeding in a circle at full throttle – that also seem like harassment to me, but don’t quite fit this definition. But I think this is a start. Also, no swimming with dolphins – for profit or not.

The regulations go on to state that their purpose relates to the permit system provided for in NEMBA, to registration and legislation of facilities like wildlife breeders and rehabilitators, and to the regulation of activities defined as “restricted”. The regulations also provide some further stipulations regarding boat-based whale and dolphin watching, and white shark cage diving. It is specifically stated that the regulations are to be applied in conjunction with CITES, international regulations which circumscribe international trade in wildlife (and in this way achieve protection for some species).

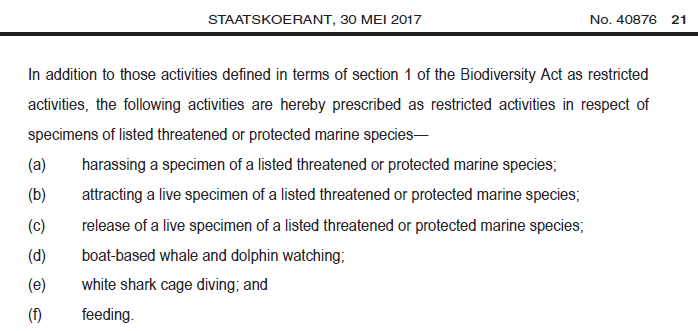

Page 17-18 defines restricted activities (in other words, activities which you either cannot do at all, or for which you need a permit).

Page 18 further clarifies that a permit is required in order to carry out a restricted activity, and the regulations go on to define various types of permit in terms of their period of validity and other criteria.

There is a lot more on permits, the risk assessments required before they can be issued, and criteria to consider in permit applications. (Does the applicant have a record of offences under NEMBA? Are there objections to issue of the permit? And so on.)

Page 38 mentions that in the case of a captive breeding or exhibition facility, no whales, dolphins, seals, sea birds, white sharks, basking sharks or whale sharks may be introduced from the wild. If I read this correctly, this puts paid to the restocking of dolphinariums with wild-caught animals. Also a start. If you are interested in this aspect of the regulations, I would encourage you to go through the document yourself.

There are some more good provisos aimed at the regulation of wildlife sanctuaries, but that isn’t my main area of interest here.

You may have picked up that some of the activities defined as restricted may be required actions in the event of a whale stranding, for example, or the entanglement of a seabird or turtle in fishing lines. What to do?

The regulations make specific provision for the cases in which one might need to handle, move, or even kill an animal listed as threatened or protected. Only those individuals or organisations which are in possession of a permit may perform any of these restricted activists; this largely precludes members of the public from assisting in any significant way at whale stranding, for example. I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing.

Finally the regulations turn to white shark cage diving, and boat-based whale and dolphin watching. I am not sufficiently familiar with the existing regulations of these two industries to comment on what is different or new here, but it is interesting to read through the provisions for each. They seem well regulated. Free diving with white sharks is specifically forbidden. Additionally, as item (e) below states, even if an operator is in possession of a cage diving permit, this does not permit them to chum (“provision” or “attract” sharks) anywhere else.

List of Threatened or Protected Marine Species

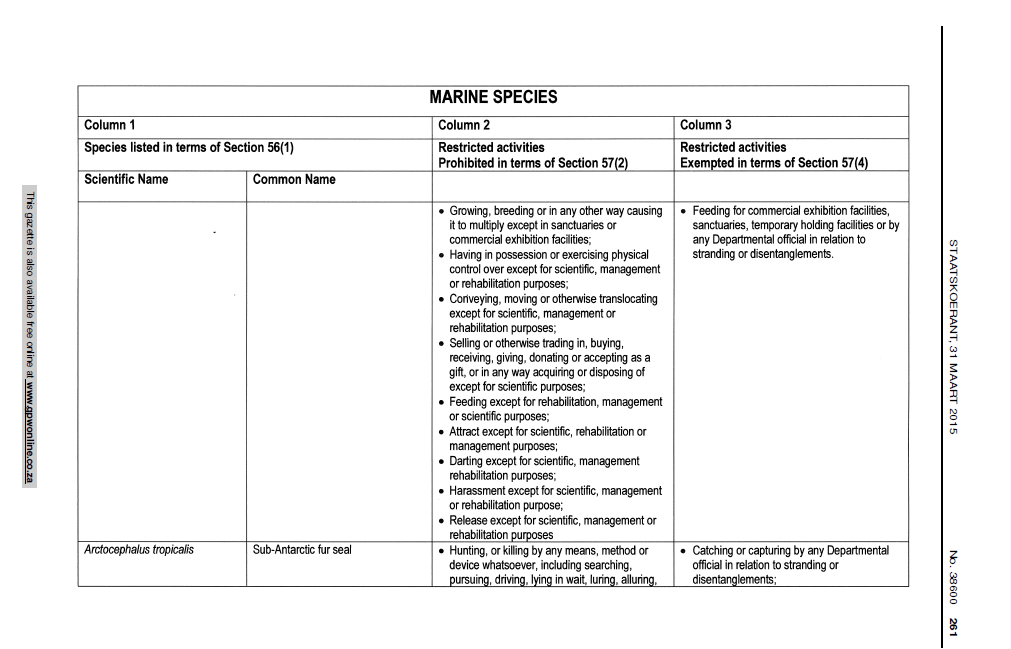

The second part of the Government Gazette publication on 30 May is a list of threatened and protected animals. This list mentions fish, whales, seabirds, turtles, and even hard corals. This document (pdf – page numbers below refer to this file) has a very particular tabular layout.

Column 2 defines the restricted activities that are prohibited in terms of section 57 of NEMBA (see above). Column 3 provides the exceptions to that rule. [This column of the table mentions section 57(4) of NEMBA – you’ll see my extract above only goes up to (3). I suspect there’s an amendment to the act that I haven’t found that includes this item.]

There is very little variation in the list of restricted activities (column 2) across all the animals and birds; whales have the most interesting list of exempt activities (column 3), which is why we will look at them as an example. This table is from pages 138-139. Click to enlarge.

Column 2 of the table above defines all the things you can’t do to whales – the “restricted activities”. Column 3 lists a whole lot of terrible-sounding things that can be performed under certain exceptional conditions, in the event of a whale stranding itself on the beach, for example.

This is a good time to practise using the definitions. Notice that column 3 allows “harassing [of the stranded whale] by any Departmental official.” This does not mean that someone from Environmental Affairs is allowed to go and prod a stranded whale with a stick, or throw sand at it. We are talking about harassment in terms of the legal definition above, and this may include “disturbing” the whale, or approaching closer than 300 metres on a boat, for example.

If you’re interested to go and look, the pages of the species list pertaining to seals and their relatives is on pages 141-144. There are no special provisions to worry responsible water users, and the definition of seal harassment as shown above (approaching a colony closer than 15 metres in a boat or 5 metres as a human) is I think entirely reasonable.

Finally, here’s an extract from the permit application form. I include this to show you that all the restricted activities for which permits are required are pretty extreme, and not things that your average recreational diver would reasonably want to do.

This has been long, but I hope helpful. The regulations aren’t open to comment (I think I may have missed that earlier this year or last year… oops), they are final.

Energy and advocacy is best directed towards things that the diving community can have an impact on as a collective voice, and in ways that will have a chance of success. In other words, perform actions out in the real world, and align yourself with organisations that do real, scientifically informed conservation work.

I’m sure you all can think of other ideas, but I do have one suggestion regarding a species that isn’t listed here. The sevengill cowsharks that we see at Millers Point aren’t protected (they are “data deficient” on IUCN Red List). If you feel strongly about them, can I suggest as an easy first step, writing some letters (the letter in that link is out of date due to ministerial shufflings, and shark finning in South African waters is banned but this is poorly enforced – but you get the idea).

Once again here’s a link to the regulations, and here’s a link to the species list. Both are pdf files, hosted on this site in case the Government Gazette links above break one day.